Chikaogwu Kanu

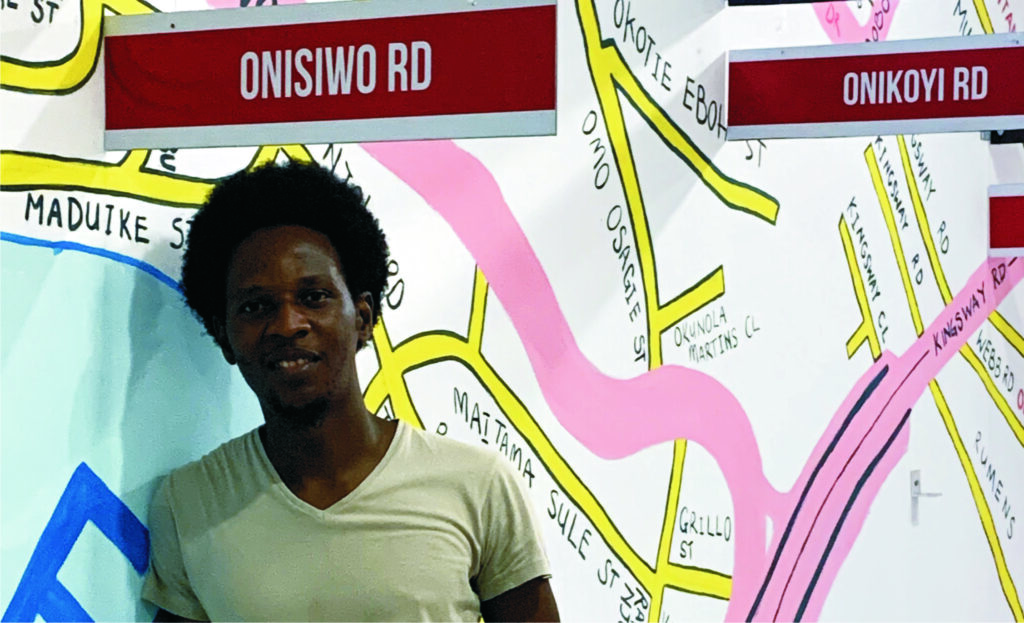

Akomona (Direction) is the theme of Tobi Animashaun’s recent debut solo exhibition that held at the Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA), Lagos, from June 5 to July 30, 2021. Akomona is a triptych art project that “merges sound installations, mural and paintings into a sublime presentation”, and “invites the audience to a state of retrospection that exalts the necessity for preservation, the preeminence of direction”, and the significance of identity in the socio-political, cultural, religious, and economic lives of our nation.

It “investigates direction, destination and place as a bearer of evidence and the lack of it using the device of street names as a backdrop and a pointer.” Akomona, therefore, explores the underlying import of street names as “symbols and relics of memory” which helps us to understand our history that are laden with “experiences, wars, victories, trade, challenges, successes and failures.”

In other words, it underscores the significance of documentation in the development of our nation, and the need to imbibe this culture that is apparently lacking. The logic of the project and its style of delivery also gives one a sense of the infinite nature of art.

The exhibition is a configuration of a mural map of old Ikoyi comprising 23 (non-exhaustive) street names that have been renamed, sound installation of pedestrians and commuters, and the “portraits, interlaced with [the] rechristened street names.” The street map of old Ikoyi covers half of the entire gallery space. While the mapping is executed directly on the gallery wall space, the mapping extension on the floor is done on a tarpaulin-covered floor.

The street names in sign posts are fixed directly on the wall, while the pixelated paintings of the personalities the streets are named after such as Adekunle Lawal that hang on the wall, “become characters in the portraiture.” According to the artist, the map signifies direction, documentation, and history. Both the old and new street names of the selected 23 streets “are not just tools for navigation, but an archive of national history.” that “keep records of experiences and feelings of both old and new residents of that area.” Sound art investigates “recordings of pedestrians and commuters” as a kind of documentation to illustrate its importance in the journey of life, and the dire consequences of neglecting this essential tool of life. The pixelated paintings on the other hand, represent how lost, confused, and retrogressive we are as a nation due to the apparent lack of documentation culture.

The whole notion of the display indeed gives one a sense of ephemerality – the impermanence nature of things which is central to the message the artist is communicating, and the need to arrest the vital aspects of this transiency through documentation. I agree completely with this objective of the exhibition. The ephemeral mode of expression influenced by the postmodern style of installation is accentuated by the fact that the works on display will eventually disappear through the repainting of the wall that bears the mapping mural, rolling out of the tarpaulin floor mapping, and dismantling of the street names installation. This temporariness evokes the idea of the true nature of life and society that is in a constant state of flux. For instance, even the street mapping – the subject of this exhibition is changing while the exhibition is going on. This underscores the significance of freezing and/or pausing method adopted by this show as a method to capture and appreciate some of the passing beautiful moments of life and society through documentation. And this is the scenario the artist invites us to ponder about in the context of documentation and development in Nigeria, and the continent of Africa as well.

The challenge of documentation in the development of Nigeria can better be appreciated when one considers how lack of accurate census figure in Nigeria occasioned by poor documentation culture has continue to plague meaningful development in our country. The conduct of census in Nigeria has often been marred by irregularities and malpractices occasioned by poor culture of documentation and ignorance about the significance of accurate census figures to national development. And this has no doubt undermined meaningful development of Nigeria since independence. According to Abraham Okolo, 1999, “Census-taking is a very sensitive issue that has remained intractable in Nigeria.

A series of censuses makes it possible to appraise the past, accurately describe the present, and estimate the future. The lack of [it] severely limits government capacity to plan, manage, and evaluate the tremendous investment in its economic and social programs.” This assertion partly explains in unequivocal terms the reason meaningful development has continued to elude Nigeria, as efforts to get accurate census figure for the country since independence has remained a mirage. This problem highlights the importance and the urgency of the message Tobi is trying to pass across through this exhibition. There is therefore, the compelling need on the part of everyone – the citizens, and the political leaders as well to rethink this poor culture of documentation in order to set records straight so as to move our nation forward.

The uncanny subject of this exhibition, and its style of rendering also highlight the exciting nature of contemporary Nigerian art that is in a constant state of change in line with the ideals of postmodernism. Postmodern philosophy encourages freedom, experimentation, and the risk of discovering art in weird things and places as exemplified in this Tobi’s art of street mapping exhibition. This freedom of conceptualisation and execution of aesthetic ideas also call to mind the concept of “art can be anything” as espoused by El Anatsui, a Ghanaian/Nigerian sculptor best known for his monumental crown cork installations that have brought him global recognition in the art world. This concept argues that “art works and discourses could be generated literarily from anything. This theory describes art as belonging to the method of intellectual inquiry that applies divergent thinking.” The implication of this concept is that there is no limit to the things or experiences that can be turned into art. The answers to artistic problems are, therefore, open to infinite possibilities, as Tobi has demonstrated in this exhibition, by creating aesthetic experiences and critical debates out of something as mundane as street mapping and street names. The exhibition can be considered successful because its conceptualisation and delivery indeed exemplifies transiency and freezing experiences of life that the artist basically sets out to use in calling our attention to the nation’s poor documentation culture, and the need for a change of attitude.

Tobi Animashaun, a self-taught artist, holds a bachelor of Arts degree in English Language from the University of Lagos. He has participated in a series of group exhibitions such as: Artwyn: From Eko with Love series (2013), The Root exhibition, 2017; Lagos Biennial: Living on the edge; Threshold, 2017; Retro Africa: Generation Y, 2018; Arthouse Contemporary: The Affordable art auction, 2020, C.I.A. (Cultural Intellectual Association, Lagos); A New Kind of Alchemy, 2021, among others.

•Kanu, a PhD student of Art history at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, writes from Lagos.

This review was first published in THIS DAY, Sunday Newspaper, April 10, 2022.

https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2022/04/10/city-mapping-and-stretching-the-frontiers-of-art-2/